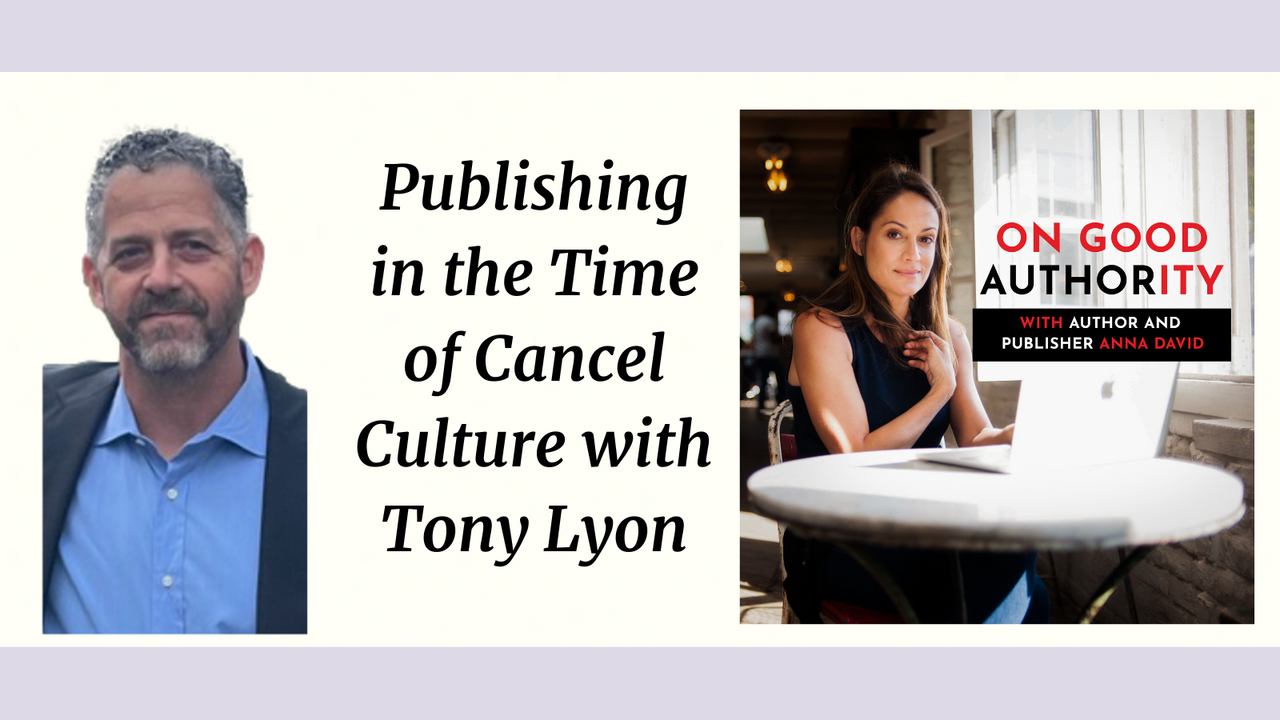

Publishing in the Time of Cancel Culture with Tony Lyons

Tony Lyons, the CEO of Skyhorse Publishing, is not one to shy away from controversy.

He's known, in fact, for picking up books from other publishers when the authors are "cancelled."

I'll be honest...I was scared to record this conversation because the times we live in—where anything you say if you don't subscribe to a certain way of thinking can be an opportunity for others to take you down. But the fact is, I believe that everyone should have a right to say what they believe, even if it's not what I believe, and that a mob mentality approach to scandals doesn't help anyone.

And so we got into all of it—how Skyhorse picked up Woody Allen's memoir after Hachette cancelled it, the ways some of his books have lost "likes" when they've been squashed, the money Vanity Fair must have spent punishing him for the Allen book and more. We also talked about which media opportunities can really move the needle in terms of book sales, why newsletter lists matter, how editorially influenced the New York Times bestseller list is and just how few sales you can have to make it on the list...among many other topics.

Brace yourself for this one.

DOWNLOAD THE PODCAST ON ANY PLATFORM HERE

APPLY FOR A CALL TO WORK WITH LEGACY LAUNCH PAD HERE

TRANSCRIPT:

Anna David: Thanks for doing this, Tony.

Tony Lyons: Sure, thanks for having me.

Anna David: Long overdue. As I was telling you a starting to tell you, I'm a great admirer of your let me just say, audacity, your bravery in the face of canceled culture. And as someone who lives in Los Angeles and has grown up a certain way and has certain beliefs, it actually like, literally, I'm scared talking about this because it's a crazy time we live in. So, the reason I'm saying this is that your company has published many books that the more traditional publishers have either been scared of or literally cancelled, and you have scooped them up. Let's talk about that.

Tony Lyons: Yeah, first of all, I mean, I would just like to say that in many cases, we published books on both sides of the same question. So what I what I really liked about that, is that, you know, if you're going to cancel somebody, I think that you ought to at least give them an opportunity to give their point of view, because how does how to viewers or how to readers or people watching movies, how does anybody figure out whether they agree with something or not? So we don't want to live in a world where people just tell us what to do or what to think or what to read. We want to hear arguments. So make your best argument. And if you have a better argument, you don't need censorship, you don't need cancel culture, you don't need to deep platform people. I mean, why take somebody off Twitter? Even the president, even if you hate the president, even if it just gives you this sort of visceral reaction, and you just think I would do anything, to not have to listen to his tweets in the morning.

Think about what it means if you can kick a president off of Twitter, you know, that's the ultimate power, then that you can just silence anybody. And then once that power is kind of created, how do you ever rein that in? So how do we know that it's not the government deciding that they want to go to the Iraq War, right, and they're gonna just pull all the strings, they're gonna use a kind of power, that no dictator in history has had, a kind of like, power for propaganda, and for censorship and for deep platforming. Where they can take sort of like a CIA official and out her, or they can control what people find on Google, or Amazon can not allow you to advertise for a certain book, or they can actually take the likes off a book. I mean, just the granular nature of it. Like they can get so deep into censoring something, because they've been told to, so the government can kind of collude with big tech companies to get out a certain message. And there's this great document that was put out by the Surgeon General in the fall of 2021. And what I mean by great, I mean, it's a scary, it's like reading 1984, right?

So it's about countering health, misinformation. Sounds like a great thing. You know, you want to know the truth, you, you know, so that you don't make bad decisions, right. But the but the scary part of it, is that it's all about strategy. And there's no definition of what misinformation is. So the problem is that misinformation is a great word. It sounds like you're being helped. So you have misinformation or disinformation, or violence, or you call somebody like a domestic terrorist, or you call them a conspiracy theorist. But many of the great revelations that book publishers or investigative journalists have made were conspiracy theories till they were proving true. So what I think we need in this country is as much speech as possible, as much open dialogue as possible. And then people really know what they're deciding on people really know why they're making decisions. It's not just based on what they've been pushed towards or threatened towards or forced towards. Anyway, I could go on and on, but I'm gonna go and have some dialogue here because I talk about dialogue and debate.

Anna David: Exactly. I must dialogue too, although this is one where I really do want you to talk about because I just find it very fascinating, and I've never had someone like you on the show. And, you know, I think about it, like I said, I live in Los Angeles. I didn't quite understand the bubbleness of it. I wouldn't if I didn't have this entire community of entrepreneurs, many of whom live in Texas and Arizona and other places. And so I just sort of thought, well, everybody smart thinks this one thing. Of course, that's what everyone thinks. Then I'm like, wait a minute, I'm seeing these friends. They're very smart. And they think this, and I think it was the moment of the artists leaving Spotify, because of what Joe Rogan said, where I'm like, what is actually going on here? And so you have not been afraid to speak out about this ever, or have you?

Tony Lyons: Yeah, so I don't feel afraid of publishing any of these kinds of books and of saying the kinds of things that I that I say, but I mean, for me, it's more that I'm more afraid of the alternative. Which I think is living in a country or in a world where I can't give my point of view and where people can't publish books on certain things, or they can't make comments about certain things. And I think anything for I would say just about anything ought to be on the table. But there's so much now, that's not. I mean, there's so much where if you say something that's just a little bit off the narrative, then suddenly, you're this terrible person? So but let's see, how would I would like to say this? Well, there's a book that I'm considering publishing, so I'm not going to give details on it. But this book has to do with the transgender swimmer issue, you know, which I think is a fascinating question. You know, so you've got swimmers who are born, I mean, I don't know the right lingo. So I'm going to, you know, put myself in a bad position quickly.

But I would just say that, that there are people who have trained their entire lives who are smaller, weaker, physically, for whatever reason, and they are the best in the world at what they do. And then you get somebody else who comes in, that weighs 50 pounds more, who has much more muscle mass, and beats them easily. So I think, as a publisher, not really taking the role of trying to tell anybody, what is reasonable there. But I think at the very least, it's an issue that people can talk about, that they can wrestle with. And so you know, where I come out on, it doesn't really matter. Yeah, so what I think and what really matters to me, is that it has to be okay to have that conversation, and to have an uncomfortable conversation. And if you're going to be a publisher in the first place, you ought to be willing and excited to get involved in those complicated conversations. Those conversations that people don't really want to have at dinner parties, because somebody is going to throw their drink and march out. But why do you want to publish a book?

Why do you want to read a book that just has everything that you agree with it? I mean, what's the possible point of that you would have a better use for your time. So you should be reading things often that you disagree with. And if your position is really strong, then it can stand up to other arguments, you don't have to then say, you know, my position is so weak. Because censorship really is all about weakness. It's about not feeling that you can make a stronger argument that will convince people. So you want to force people to see things your way, or you want to forbid people from reading certain things, because they're so dangerous. And so, I don't think that that's true. And I don't think that that's good. And I think the world is better with as much dialogue, as much conversation, as much competing ideas as possible. And that the marketplace of ideas is a pretty good place for people to kind of come together. And that now we have kind of two Americans.

And I think lots of that comes out of this sort of like, well, we're only going to watch certain TV shows, we're only going to read certain books, we're going to try to stifle any kind of other point of view. And then how do you ever get closer to the other side because you can't hear their point of view? You're just subjected to propaganda from your own side, from your own people telling you that these people are evil, but you can bet their people are saying the same thing, that you're evil. And it just can't do that kind of half the country is, is brilliant and wise and the other half are idiots. I mean, that just isn't true, it's convenient for both sides to think of the other side, like that. But I would like to as a publisher be in a position of seeing more possibilities for people coming together.

Anna David: And so, how would you say traditional publishing is broken today?

Tony Lyons: Yeah, so I think that part of it is that is that there's so much fear of any kind of controversy. So that you can have a big publisher like, Hachette sign up a book by Woody Allen that they really like, that they say they really liked. That even, a couple of weeks before they cancel it, they come out and they say, Look, we're really sorry, people disagree. We think people ought to have the right to disagree, we think, you know, it's fine that people go outside and pick it where we're publishers were for free speech. But we're still going to publish it. Because we really like it, we signed it up for a reason, nothing's changed, since we signed it up. But then the stakes just got higher. So the stakes got to well, sort of like you, you said, where some musicians started to pull out of Spotify.

People started to say, well, we're going to pull out of Hachette. And so people are not going to work there. They're not going to publish there. And so I think the problem with caving to that sort of pressure is that there's no logical end to it. It is that you've sort of created a monster there, then where anybody who has a little bit more power can just decide for you what you're going to do what you're going to say what you're going to publish. And so I'm more afraid to get back to your question. I'm more afraid of that kind of world than I am of any consequences. I mean, right after I published the Woody Allen book, I was contacted by Vanity Fair. And I was thinking, Well, you know, what's my punishment gonna be? There were a lot of very angry, powerful people thinking we worked so hard to get this book canceled.

And they then said, well, what did we really win by getting it canceled? So Skyhorse published the book two weeks earlier than Hachette had planned to publish it. So all of that work that they did help them in no way at all. So there were people who were angry. And I was the face of that decision. So Vanity Fair wrote an article on me, hard for me to imagine that that article came out of anything other than my decision to publish the Woody Allen book, which is Apropos of Nothing. So my feeling there is that is that I don't really care that they wrote that article. But I was fascinated that, that would happen, because nobody at Vanity Fair knows who I am. Nobody at Vanity Fair knows who Skyhorse publishing is. I mean, none of the readers there, they didn't review our books. I didn't know anybody there socially, there was no connection whatsoever. There's nothing in it for them, they're not going to make any money off writing that kind of story.

They're not going to get more readers. So why would they do that store. So the only logical thing for me is that it's kind of a punishment, it's a part of the whole sort of cancel culture, and then they called it something it was a really terrible title. I can't quite think of it, but it was just sort of an awful title that made Skyhorse look like this terrible place. But then you read this endless article that took them months and months where they interview so they treated me like I was somebody world famous. That they would want to spend literally hundreds of 1000s of dollars researching and interviewing people to find out what the backstory is, but the whole story is that they were upset that I published Woody Allen's book. Which is, you know, one sentence.

Anna David: Yeah, it's very interesting. I reread it this morning. And so I started working in media in the 90s, the workplaces I've been in I've had phones thrown at me, I'm trying to discern what is the disturbing part and there's even this thing about Oliver Stone, I know I live in Hollywood, this is. This is what is, the story and of abuse that I have put up with in the workplace, and then I hear about things, and I hear comments, and I absolutely my heart goes out to women who have felt, who have had been a terrible, terrible situations. I have been too, when I hear about situations that do not sound terrible in their description, and I immensely have a lot of sympathy for it, it just makes me feel like, what world am I living in? So yeah, it's a fascinating story that ultimately didn't say very much. And did you know that's what was gonna happen? It was probably worse than you expected.

Tony Lyons: So there's sort of a playbook for all of these kinds of stories, which I didn't really know at the time, but I'm perfectly fine with, which that they sort of start off by telling you, oh, you've built up this great company, we're so impressed with it. You know, what are your favorite books? What drove you to start a publishing company? How have you been so successful? All of those kinds of things. And then they go on with that sort of stuff for an hour or two hours, and then they get into something else. And then the whole story is the other thing, which is fine. It's a journalist strategy. So was it worse than I thought it would be? No, it was exactly as I thought it would be. Once I really got into it, because I decided to engage because I'd never been in that position before.

And part of what I like about being a publisher is this incredible journey, that I feel like I go on with the book or with each issue that that comes up. And so this was just another part of that journey. And I wanted to kind of embrace it fully, and talk to them as much as they wanted to talk. And we wrote dozens of letters back and forth, where they made certain allegations that they had heard and from somebody, and then I said, no, no, that that's not the story. Here's the document, here's another person you should talk to. But it was really interesting, like I said, because I'm nobody in the publishing field. I mean, in the sense that none of their readers know who I am. None of their readers care about us. Almost none of our books would even appeal to any of their readers. So what's the interest that they'd be willing to spend so much money on? Other than to sort of punish somebody.

Anna David: Do you think it works as like…I mean, this is I know, we're not using names like Ronan Farrow, look what we did. Like, they get points for that? Or it's just they're mad and they want revenge?

Tony Lyons: I think that they, that whoever sort of started it, and you know, it might have been Ronan Farrow, I don't know the details. So. But I think that that's the kind of thing that they just sort of thought about doing, passed it from one writer to another, but they really wanted to kind of get it done. And then I think it just took much more time then they thought, and they probably thought of canceling it. I mean, I've been involved in some long, complicated projects, books that have gone on for years. One that was I think there was a co writer, and then the co writer writer dropped out and wanted to write a separate book. So it was a project like that, that I just think went on and on for a while. But it was fascinating for me just to kind of take part in it. And also just to see what they were going to possibly come up with, you know, because I had no idea what their what their conclusions were going to be. It was clear that that they were bias that they were trying to get a specific store. But I was curious what they were going to really get and so you, you tell me what did they get?

Anna David: It was a lot of words. And I was trying to understand what was super interesting about them. I don't know if you read it, you were like, wow, I'm a lot more interesting than I thought. They, you know, really made a lot out of, well, I didn't know I didn't come at it from your perspective of knowing Oh, this is specifically about the Woody Allen book. I figured it was about a bunch of the books, honestly. But it's interesting. There was a thing this week and now I can't remember but a Cuban writer. Did you hear about this publishing scandal this week?

Tony Lyons: No, tell me I’ve been really busy with it with a couple of books that are coming out later this fall.

Anna David: Okay, I will not be able to speak ignorantly about it now, because I don't really remember the details but I can send you afterwards basically what I think happened. Cuban writer said something thing about woke white women in publishing, who worked in publishing, and there was a huge Twitter drama. And a lot of smart people are going thank God, it was a Cuban guy. I'm pretty sure, thank god somebody said this, anyway, I'll send you the stories. But so in terms of publishing, I mean, because the way traditional publishing works is there's no research, there is no studies, you know, there was this trial a couple months ago that sort of put it out into the world with people who work in publishing know, which is that it's all guess work. Do you think that's true?

Tony Lyons: Do I think it's all guesswork? I mean, I think that it is true. And I've looked at lots of the old book publishing cases where, you know, there's a question of, does the publisher have a duty to sort of really dig into the details of each book that they publish? Not really practical, you know, you're sort of engaging the author to be the expert. So you might read a book for libel. But you might not be able to verify every statement in hundreds and hundreds of four or 500 page books. And so there is no legal obligation to do that as a as a book publisher.

Anna David: Yes, true. And I remember with A Million Little Pieces, that was right, when I sold my first book that that that came up. But I mean, in terms of book deals, in terms of what's going to be successful in terms of the madness of how it works, if we're talking about like the Big Five, do you think it makes sense how it works?

Tony Lyons: No, I mean, I think that the big five publishers now are generally just playing it really safe. So they have a lot of money, they have a lot of power. And they buy the biggest books by the most famous people and they make 80 or 90% of their money from those top titles. And many of them are, you know, second or third or fourth books from people whose prior books sold really, really well. So it's become much more of a science. I mean, I know that in the recent court hearings, there was lots of talk of publishing, being really random. I'm not sure what the logic there was. But you had people from the biggest publishing companies in the world, saying that it's just sort of the luck of the draw, that you can pay $5 million for a book and you can sell 20,000 copies. You can pay nothing for a book and you can sell millions. I don't really believe that that's the way publishing is run now. I believe that the bigger companies, generally, when they're not, sort of censoring certain topics are run by people who have MBAs and you know, are really good with numbers and are making really smart business decisions?

Not really publishing decisions, you know, where I don't think the top people that most of the big five publishers are reading many books that they're looking at spreadsheets. So and they're running billion dollar companies, you know, there's a logic to that. But on the on the censorship side, I find it to be just sort of a really bad time for book publishing. And I think we're going to come out of it. I mean, I think that a lot of the top people that big publishing companies don't really want to do it. And they do it mainly when they feel forced to. So I don't think those decisions are coming from the most powerful people at the company, I think they're coming from other people who are putting them in a position where it's a bad business choice to make the decision that they want to make.

Anna David: Yeah, yeah. So tell me where Skyhorse fits into that?

Tony Lyons: Well, on the on the censorship side, it's, it's very easy to see that we are going to keep publishing books that are going to make some people angry, that are going to sort of stir things up. Many cases where we're going to publish on both sides of the same thing. We did some books during the pandemic that were censored. We did a book called The Case for Vaccine Mandates. And then we did The Case Against Vaccine Mandates, and the case against was censored everywhere, and was taken down from all kinds of platforms. So we had a whole bunch of cases like that we're doing both sides and where the other side of the argument was just made to disappear. So I think we're going to keep fighting those kinds of battles and we've been pretty successful in pushing that.

Anna David: In terms of that, is it literally like on the platforms, you'll see it's there on Amazon? I don't know if we can name companies, and then it's gone the next day, something like that?

Tony Lyons: Yeah, yeah. So there definitely were plenty of cases where things just disappeared.

Anna David: And could not be found on those platforms anymore?

Tony Lyons: No, I mean, there's been a ton of that, during this this last two and a half year period where if you counter something that's been put out by the government, the decisions were often kind of made by algorithms. So I don't think there's anybody to talk to, or to argue with. But there have been some really, really terrible things have gone on. So there have been lots of books where the positive likes on Amazon, have been taken off. And I'd never heard of that. I mean, so I'd so I say lots of books, and I assume that it's kind of a, it's a program that is supposed to fight misinformation.

Anna David: So you mean remove news, or just like five stars or whatever?

Tony Lyons: No, I'm saying that the actual likes so. So we had one, one book by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. called The Real Anthony Fauci, really provocative book, but it had 2194 citations, it had a blurb by a Nobel Prize winning scientist. So lots of people disagreed with it, but they didn't disagree with it on the merits. Like, there was nobody, no newspaper, no TV show came out and said, oh, there's a citation on page 85 that is wrong, or that it claims that there's a peer reviewed study, but there isn't. There was none of that, that it was just that it was taken down from platforms. So there was a whole kind of program for books like that, which I think was sort of scary to watch in action. And that was that you would see that the author would get a hit piece written on him or her in the New York Times, or in Vanity Fair or in many other places.

But there'd be no review of the book, even if the book was selling really well. So that was a book that sold more than a million copies, and in the three different formats. And it got no reviews in any major newspaper in the country. The New York Times in its first week, it far outsold any other hardcover nonfiction book, buy 10s of 1000s of copies. But the New York Times made another book than the number one title, because they just didn't like that book. I mean, that's my analysis of it. There's no other argument that I think makes sense.

Anna David: It was on the list, it was on the New York Times list, it just wasn't the number one spot.

Tony Lyons: Right. So they made it number five. But, but they made their own book, which was the 1619 Project, which was written by a New York Times writer about a project that was funded by the New York Times. So you get the feeling that when it comes to books that the New York Times doesn't like or conservative books, or just any kind of narrative that they're not on the same page with, they are going to treat it differently. So there it's not really just a bestseller list. It's a New York Times recommended reading list. So people in publishing know that. But the general public doesn’t.

Anna David: The Exorcist writer sued them: William Bladdy. Because not The Exorcist, but Legion, his other book was but and they and they came to court and they said, “Hey, this is actually an editorial thing.” And the court sided with them.

Tony Lyons: Yeah, I don't think that the court should have…you know that they're calling it a bestseller list. They're not calling it a recommended reading list.

Anna David: Right. Right. But I also did want to talk about, so Skyhorse. How many books do you acquire a year? Can people just submit? How does that work?

Tony Lyons: Yeah, sure. So we published something like 500 books a year now, the most that we ever published in a year was just under 1200. That I think was too many. It's just too much work. And I and I get involved to some extent in each of those. So if you try to, I mean, to many of them, it was a very, very small involvement, but some involvement, and if you think about that four books each day or you know, three and a half books each day. That's just not going to work. And I like to be more involved. So now we're gonna publish something around 400 bucks per year. And I'm happy with that number. So yeah, and anybody can send us books, probably a third of our books come from agents and something like a third are books that we can't see above and we seek people out where we think it's a topic that that we'd like to publish a book on. And then about a third are from just people sending us books.

Anna David: Yeah, and they can just do it online, they could just go to the website and send books. And I did want to talk about this has been fantastic. I did want to get into this conversation you and I had this other time about media, and I will always proclaim, like, you know, TV doesn't sell books, it gives a lot of credibility, but it doesn't really sell books. And I said that to you. And you were like, well, it really depends. And you had these two examples, what were those?

Tony Lyons: What I think really sells books now…and we've seen that for many of our books is, you know, a mailing list that the author or that organization has put together. And that if you write a certain kind of letter, and there's a strong enough nexus between your mailing list and the topic of the book, we've had cases where a mailing list of, you know, 500,000 people has sold 30 or 40,000 books. And that's a really, that's a shocking correlation there. Because as somebody in publishing, you know, people outside of publishing my thing, well, 30,000 books isn't that many books, but to put it into context for viewers, the number 15 book on The New York Times bestseller list about at the end of the summer, was around 3000 copies. So, I mean, there were other books that didn't make the bestseller list that sold 30,000 or 40,000. But that's the story that we've already covered. So but it can be three or 4000 copies to make the New York Times bestseller lists. So if somebody has a mailing list, and they can sell 30,000 books, they can get on to certainly the Wall Street Journal bestseller list, USA Today, Publishers Weekly. And then then you know, the times is going to be a be a toss up.

Anna David: Right. Right. So newsletters are the most important. Most people obviously do not have 500,000 people on their newsletter list. But partnering with an organization is a great way to do it for 10 different places. And so but what TV shows, or other media outlets, do you think can move the needle?

Tony Lyons: So I think that really targeted podcasts are probably the best way to sell books. Now. I have watched books on a minute by minute basis for sales through Amazon. And I've watched while somebody was on a podcast and sort of looked at what they said, and then how many copies sold in the next 60 seconds or two minutes or three minutes. And I find that sort of thing. I mean, I'm not a numbers person really, I've found that to be really fascinating. And so that was if people described their book in a way that really made somebody take action. So part of the problem is that if you go on the Today Show, and it's a workout book, and you do two or three different ways to work out, I think people watching that just take that as content and they just sort of say thank you.

And they write a couple of notes. And they're done. They don't they don't want to read a 300 page book with step by step things in it, they see how you do a sit up and they're happy. So, I think that when you're dealing with a podcast, it's about something specific. And the person kind of teases what the book is all about, then I think there's a strong enough nexus that you might have 1000 people suddenly just click on their phones and buy the book. And that I had never seen before you know, even on television, I mean, I've seen cases where they were 10, 20, 30,000 copies so from a really big TV show, but that's really rare now.

Anna David: Are there specific podcasts that you can say I really can make a big difference. I mean, like I somebody had on the podcast said something like a Tim Ferriss or Joe Rogan actually isn't good because it's cult of personality peep the listeners care about them, they care less about the guests. Whereas something with like a sort of enthusiastic, inquisitive listenership that might make a bigger difference.

Tony Lyons: Yeah, I would say that the more targeted the better. So you know if it's somebody going on a Joe Rogan show that that really fits the Joe Rogan demographic really well. And it's something that he discusses all the time. And then somebody just nails that. And then Joe Rogan says, hey, this is a book that every one of you ought to read, then I think you're gonna sell a huge number of copies. I mean, he doesn't do that very often. But yeah, so I mean, there's nothing specific that I would point to that I think is great. In general, I think that there are hundreds of podcasts now. And that's a really nice thing. Because they're not hundreds of gigantic TV shows that you have any prayer of getting on. There are hundreds and hundreds of podcasts that in your niche might be just perfect.

Anna David: Well, one final thing I wanted to ask you about Skyhorse, so for people who published through you? You know, when you have so many? Are you putting marketing and PR and all of this stuff behind it? Is it dependent on the author? I know, when I did books with Harper, it was very much incumbent upon me to do a lot of that work. Where to Skyhorse stand with that?

Tony Lyons: Yeah, so I kind of want to publish people who care about selling their own books. Yeah. So I think that the age of kind of like, you write a book, and you hand it off to a publisher, and then call in six months later and say, is it a best seller yet? That's totally gone. I mean, I'm not sure that there ever was a time line like that. But in any case, now, I think it's a real partnership. And what the publishing company can do is help you leverage, whatever assets you have. So if you have a great mailing list, then what's the right letter to send to those people? Because if you send the wrong letter, nothing happens. And if you don't have click throughs in the letter, to buy the book, so what are the best practices? And I would say that even in a one page letter, there should be something like 6 to 8, click throughs, to buy the book. You should send them to a website, that maybe is the publishing company web website, send them to Amazon, but also give them a choice between Amazon, Barnes and Noble, you know, various other places.

So I think doing it like that, and having some of them be on keywords. But then having two or three places where it says, Click here to buy the book, that those kinds of things are things that publishing companies can help you with and should help you with. And the same is true even of say Twitter, I've had people tweet about a book who had 50 million followers, and nothing happened, because they say something like, my friend, so and so wrote this amazing book. But the person is a world famous personality, who may be, people like the guy because he's good looking. So those 50 million people are not going to be book buyers. I mean, they're not going to be booked buyers for a specific book. Because the followers are just people who are following that person, because of their looks, or their fame or something. It's not targeted.

So, we had that case, once where we published an environmental book, that was a really serious book. And the person who had 50 million followers tweeted that it was a great, great book, and that people ought to read it. And it was about a month after the publication date. And I don't think that book sold 20 copies in that week, with 50 million people got this tweet. But if you have 100,000 Twitter followers, and it's about, you know, let's say it's about the rain forest, and all of your Twitter followers follow what's going on in the Amazon. And they're really concerned with Brazil, and they're following the election in Brazil, and they're concerned about it, and you're coming out with a protect the rain forest manifesto. Those 100,000, that's different than Joe Rogan, or some famous persons 50 million people. That's 100,000 people care. And there's no telling what percentage of those people you can get. I mean, if it's it, good enough book by the right person really targeted, timed well, it could be 20,000 people out of that. 100,000

Anna David: Yeah, yeah. Well, this has been very illuminating. I hope you've had fun. And so Tony, thank you so, so much. To find out more like people should go to Skyhorse website. Where should they go?

Tony Lyons: Yeah, they can go to Skyhorsepublishing.com

Anna David: Well, thank you and so much. Is there anything that you wanted to add that I didn't ask you?

Tony Lyons: I would like you to tell me about what you do. Maybe that doesn't have to be on the podcast.

Anna David: These people are sick of it. No, they love me to death. It will stop it and then I'll tell you everything. Thanks, you guys. Thanks so much for listening.

CLICK ON ANY OF THE LINKS BELOW TO HEAR THIS EPISODE OR

CLICK HERE TO GET THE POD ON ANY PLATFORM